Click on pano images to view larger images

Bit of a cliché name perhaps, Valley of Fire, but wholly appropriate. Imagine fire turned to stone, indeed, that is what you will find here. No doubt, one of the most spectacular geological curiosities on earth. Yeah, make that compared to say, for example, Arches NP, Canyonlands NP, Vermilion Cliffs, or even the big hole, aka the Grand Canyon. Yeah, it really is that good. Remarkably, this unique area is part of the Nevada State Parks system.

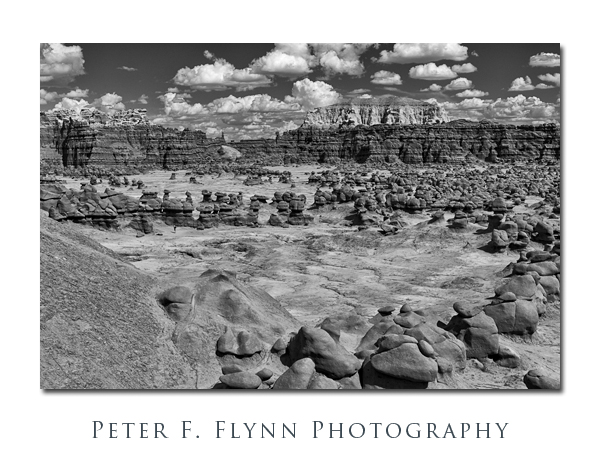

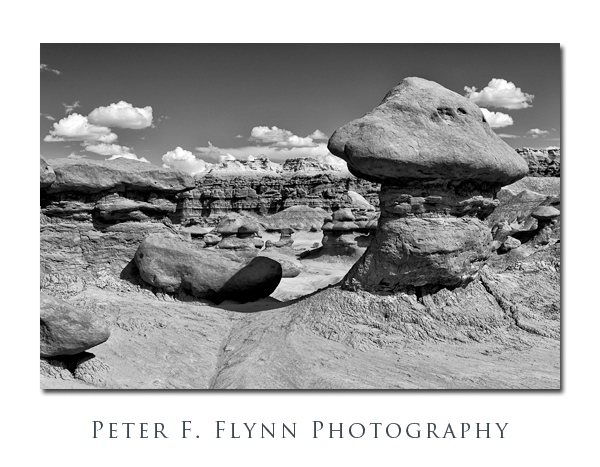

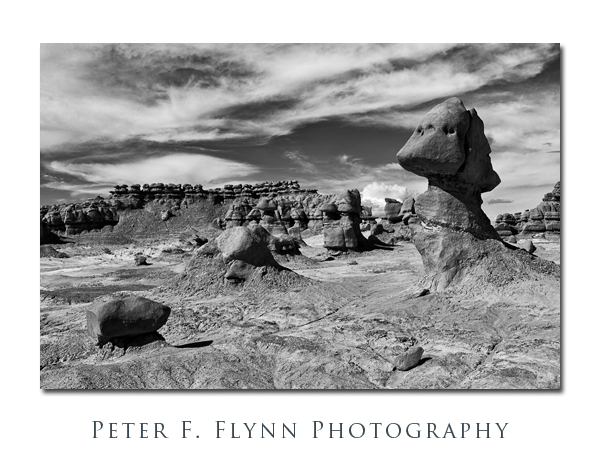

The image above was recorded on March 26 at 15:00 MDT, 2013, near coordinates 36,28.58°N, 114,31.63°W.

Of course The Valley does not encompass as much area as some of the other awesome sandstone sites – somewhere between 34,000 and 42,000 acres (the park site does not list the area, and online sources provide inconsistent estimates). For comparison, Vermilion Cliffs National Monument is over 290,000 acres…Grand Canyon is over 1.2 Million acres. The park was not even chartered until 1935 – the fill of Lake Mead also began in 1935. The Lake and Valley actually share a boundary, and since the former was made a National Recreation Area, it is interesting that The Valley remained under control of the State of Nevada.

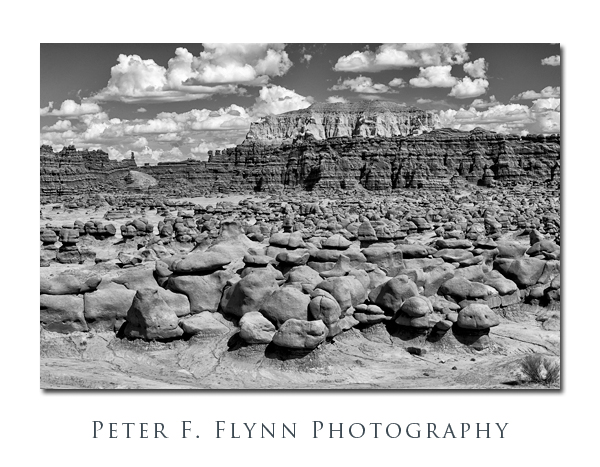

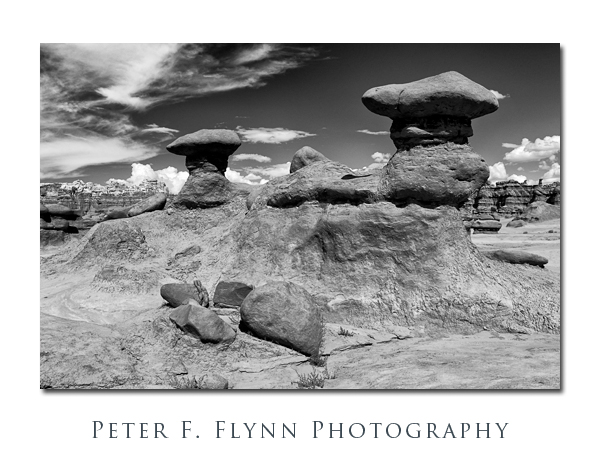

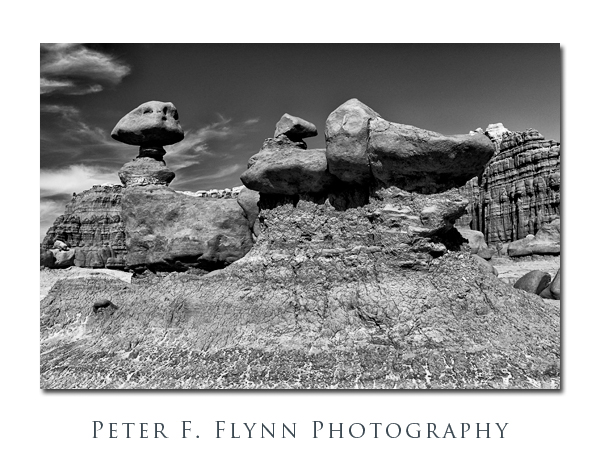

The image above was recorded on March 26 at 15:20 MDT, 2013, near coordinates 36,29.19°N, 114,31.58°W.

There are two major roadways in the park. The main highway, aka The Fire of Fire Highway, runs east-west, while Mouse’s Tank Road runs north from the junction with the highway. The roads are very well maintained, with frequent opportunities to stop safely along the way.

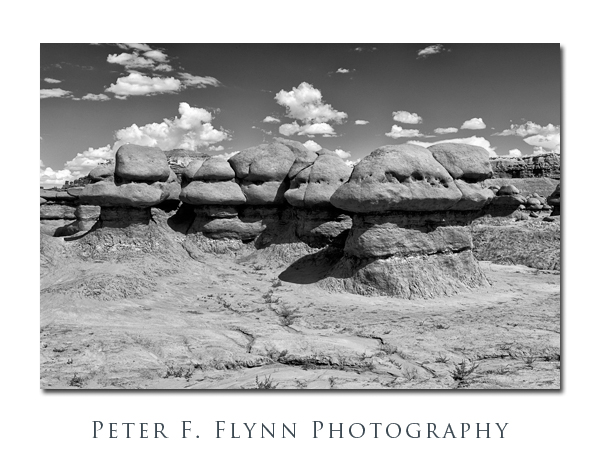

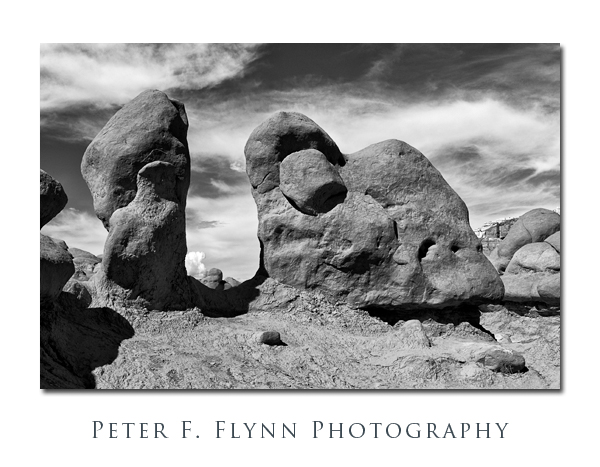

The image above of the Seven Sisters was recorded on March 27 at 07:13 MDT, 2013, near coordinates 36,25.59°N, 114,30.02°W.

The park is about 55 miles northeast of Las Vegas along I15, exit 75. Amongst the unusual features of the park is the active wedding photo biz that is supported. On a typical day, one can view about a dozen wedding photo shoots – big limousines and large wedding parties included…

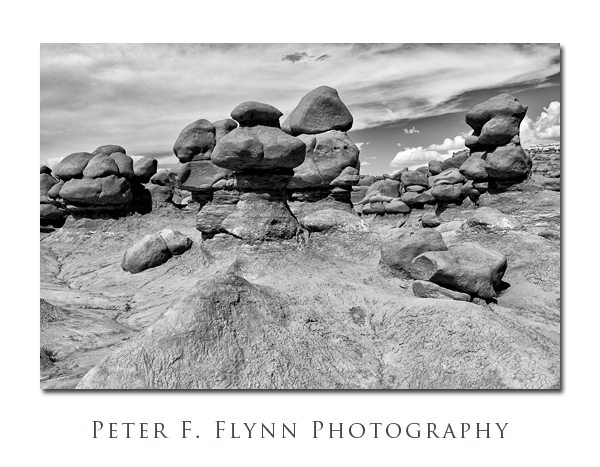

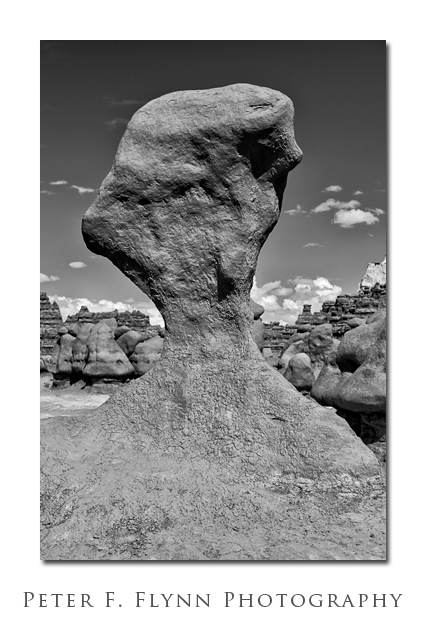

The image above recorded on March 27 at 08:20 MDT, 2013, near coordinates 36,27.74° N, 114,31.46° W.

Most of the visitors stick close to the main highway and visitors center area. Even on busy days the north end of the park remains relatively uncrowded.

The image above was recorded on March 27 at 10:36 MDT, 2013, near coordinates 36,29.18°N, 114,31.79°W.

Although this is a small park by NP standards, it is super-rich with image-able features. and deserves at least a full day shoot – frankly, two days minimum to shoot it properly.

The image above was recorded on March 28 at 07:30 MDT, 2013, near coordinates 36,25.55°N, 114,27.85°W.

Some may claim that the images in this entry have been over-amp’d. Nah, not at all, in fact if anything, I have been a bit too light on the processing.

The image above was recorded on March 28 at 08:44 MDT, 2013, near coordinates 36,27.12°N, 114,30.95°W.

The image above was recorded on March 28 at 10:37 MDT, 2013, near coordinates 36,28.95°N, 114,31.70°W.

Images in this entry were recorded on March 26 through March 28, 2013, using the Apple IPhone5 with either the native Camera App or the Autostitch Pano App.

An excellent map of the area may be found here.

Copyright 2013 Peter F. Flynn. No usage permitted without prior written consent. All rights reserved.